How a person lifts his/her feet when walking is pretty straightforward. One foot then the other. Repeat. Over and over it’s the same. At a jog or a run it’s still the same, one foot then the other. There aren’t many options considering that there are only two feet to choose from. If you were to add a foot to this pattern things would get confusing real quick. After you lift your first foot, which would you lift next? Horses (and a few other animals) have four legs and feet to deal with. Luckily, millions of years of evolution have given them four different patterns of ways to move their legs that work pretty well. We call them: walk, trot, canter and gallop. There are a few other names you might hear and I’ll get into those later, but the four patterns are the same and are in order of the natural progression in possible speeds through space from slow to fast. Think of them like gears in a car. First gear is for slower speed and third is for faster speeds–but you can with some clutch work get the car to start from a stop in third gear, it just won’t be easy. If you’ve never driven a stick shift, strike that last sentence. Before we get into the patterns more specifically there are some other possible patterns. They are rare. Most horses move in only these four ways, but sometimes you will find a horse or a specific group of horses that use a different pattern. Sometimes they are learned and sometimes they are naturally acquired. After we run through the four basics I’ll get into some of the other possibilities.

Prerequisite: Understanding Beats and Diagonals

When we talk about beats in a stride we are referring to the moment of contact the hoof has with the ground. Sometimes two hooves will contact the ground at the same time. This is still referred to as one beat. So remember, one beat can mean multiple hooves hitting the ground at the same time. In each stride all four feet will hit the ground but the pattern in which they create those beats will be different. Sometimes it will be three beats, sometimes it will be two and sometimes it will be four.

Diagonals are important because they are the basis for all four natural gaits. Look for them in a walk, trot, canter and a gallop. At some point in most gaits there will be a moment when your horse is balancing on an opposite pair (or diagonal) of hooves. It’s easiest to see in a trot but you can find it in a walk and canter if you look. The gallop is a bit of a different animal but it has its roots in a canter so the remnants of the diagonal are still seen in the uneven foot fall in the placement of the front hooves and the placement of the back hooves.

The Walk

This tends to be the slowest moving gait. It’s a four-beat gait which means in every stride there are four beats of hooves hitting the ground before the stride repeats. This is the most complicated of the gaits to understand. Just remember the basics:

Back left, front left, back right, front right. Repeat.

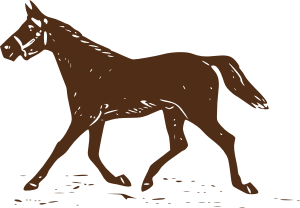

The Trot

This tends to be faster than a walk and tends to be slower than a canter. A two-beat gait using an opposite pair of hooves, two at a time. With a moment of suspension in between each beat the horse “jumps” from one opposite pair to the other. Bum Bum, Bum Bum, Bum Bum, Bum Bum. This is the easiest to understand the hardest to sit. Here’s the pattern:

Back left and front right, back right and front left. Repeat.

Below are all pictures of horses trotting, notice the opposite pairs.

The Canter (or Lope)

A three-beat gait. This is what you see and know the sound of. Ba Da Dum, Ba Da Dum, Ba Da Dum, Ba Da Dum. It’s very pretty so you get a lot of pictures and videos of horses cantering. There are two ways to do this. Because there are three beats, two hooves are going to have to hit at the same time before the stride repeats. Which two? This depends on what foot you start with. So bear with me:

- Back left, back right and front left (opposite pair), front right. Repeat.

- Back right, back left and front right (opposite pair), front left. Repeat.

To differentiate these two ways of cantering we refer to the horse’s lead.

“What lead was that horse cantering on?”

“The left lead.”

To know which lead your horse is on watch the last hoof in the stride. If it’s the left front hoof, it’s the left lead. If it’s the right front hoof, it’s the right lead.

What’s so important about leads? It’s not so important when a horse is going in a straight line (although one could argue that horses never canter in a straight line) but when a horse is turning, it will be more comfortable in the turn if it finishes with the inside leg. It’s a matter of balance. If you are falling to your left, put your left leg out to catch yourself. Same on the other side. Fall right, use your right to catch. Try skipping around and see how well you can skip turning right with your left foot in front. No so good, and you look foolish.

Below is a nice, simple explanation of the first three gaits and the patterns they follow plus a bonus backup. This guy is great with his explanation of the gaits. Check out his video on the difference between the Canter and the Lope. Loved it.

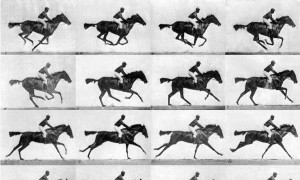

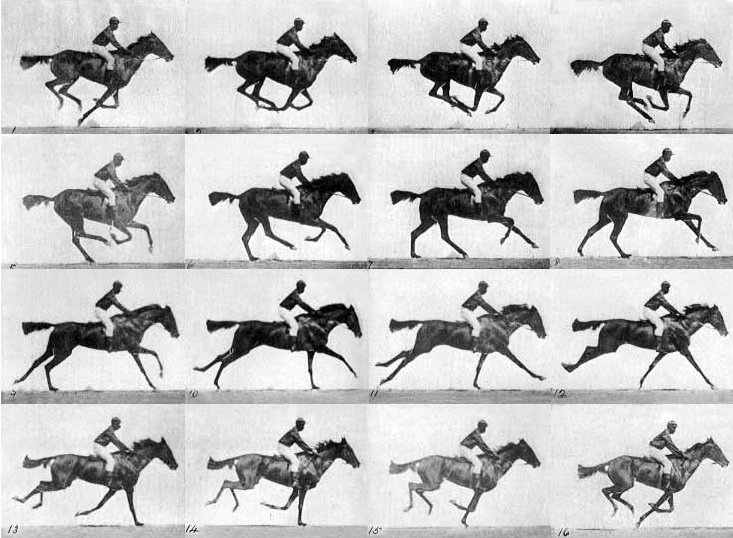

The Gallop

Now you’re truckin’. And we go back to four beats–but in a different pattern than the walk. This one is really just an extension of the canter so if you put a moment of suspension in between the opposite pair of a canter, you’ll get a gallop.

Here’s the pattern, but because you are starting with a single back leg, it can go two different ways just like a canter:

- Back left, back right, front left, front right. Repeat.

- Back right, back left, front right, front left. Repeat.

On Beyond Gallop

Now you do have some horses that can do other things. First I’ll talk about pacers. Pacing I’ll include in the natural gaits because it’s very similar to a trot. It’s just a backwards trot if you will. Instead of an opposite pair, you have the horse hitting their feet on the same side. It’s strange to see and even stranger to sit. Below is an example of what it looks like:

After pacing we will find still more. These are called ambling gaits. These horses are usually referred to as gaited horses. There are a few breeds that are bred specifically for this. When someone rides a gaited horse for the first time they usually find it to be a lot more comfortable to ride because the ambling movement usually takes the place of the trot which most people find to be the most uncomfortable of the natural gaits. Although most gaited horses can trot, the riders usually try to keep them away from it. Here are a few horse breeds that are known for being gaited.

- American Saddlebred

- Icelandic horse

- Missouri Fox Trotter

- Paso Fino

- Peruvian Paso

- Racking horse

- Rocky Mountain Horse

- Standardbred

- Tennessee Walker

How do they move their feet? There are a bunch of variations, the flat walk, the fox trot, running walk, rack… These are usually just taking a trot or a pace and changing it a little. For instance if you take a pace, then have the back hooves hit the ground just before the front, it’s a rack. Or if you take a walk and get the hooves to hit with the front just before the back, blah blah blah. It’s best to watch a movie for this one.

Last thing about gaited horses…

Gaited horses are not to be confused with the high-stepping problems of the Tennessee Walking Horse controversy. What these guys are doing with their walking horses is unnatural and horribly inhumane. You can have a Tennessee Walking Horse without making them do these things. If you want to see what I’m talking about the video below sums it up. Warning: it’s a bit difficult to watch.